Do Graduation Rate College Rankings Really Mean Anything?

Find your perfect value college

When you’re considering what college to attend, one qualification will always come up: graduation rate. Graduation rate refers to the time in which a student enters and then completes a degree at a 4-year college or university, usually expressed as a percentage: X% of enrolled students complete their degree in four years. We can find these rates listed on many national rankings, and we may think the interpretation is fairly simple; a high number is good, a low number is bad.

Well, that’s tricky. First calculated in the mid-90s, the graduation rate figures a record of full-time, first-time students who start in the fall and graduate 4 years later. Researching graduation rates is tricky. All transfer students are excluded, whether transferring out to complete at another college or transferring in to complete their degree. So, people who eventually do complete a degree, maybe even on time, don’t count. Because of that and other issues, the college graduation rate is sometimes disputed, so it’s worth knowing what it means when you’re deciding which college is the best value for you.

Featured Programs

Once it’s all over, college graduates may not care how many students graduated with them, but graduation statistics for community college students, four year colleges, and other undergraduate students makes a huge difference in how most college students choose a school for their undergraduate degree.

College Graduation Rates as a Measure of Accountability and Transparency

First off, we want to trust an institution to deliver. If graduation rates are low, that can tell us something about the school: it may mean students do not get the academic support they need to succeed, that they are disappointed by the faculty or staff, or that they find life at the school unaffordable. Note the “may” – a low graduation rate doesn’t necessarily mean any of those things, but it might be an indication of trouble.

And that may give pause to a prospective student. Extended enrollment is costly, so the best course is to finish on time. You might look at the data and see clearly that a school scores a 60% graduation rate. If, for some reason, you’re one of the 40% who needs an extra year or two, that may be an additional $8,655 per year (based on 2014 four-year public college rates) just in tuition! That’s a big hit to your wallet.

Graduation Rate as a Measure of Quality

But does a higher graduation rate make you, as an individual, more likely to finish on time? Maybe. Jeff Selingo, in the Chronicle of Higher Education, suggests there may be “peer effects” such that “being around other students who want to finish college makes a significant difference.” Positive peer pressure, in other words – a high graduation rate may mean an environment in which graduating is highly valued and encouraged.

On the other hand, many schools with the highest graduation rates are also the colleges with the most selective, elite standards. They only accept exceptional, high-performing students, so understandably, more of those students graduate. It doesn’t mean the college is better per se; it just means those students were going to graduate at any college because they were driven anyway.

Graduation Rate is Flawed but Helpful

The numbers for graduation rate come from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, which only tracks full-time students beginning as freshmen in the fall and continuing on a traditional, four-year college career. That may have accounted for most students twenty years ago, when IPEDS started keeping track, but times have changed.

College is not focused on traditional, middle-class, male students anymore, but you wouldn’t know it from how the National Center for Education Statistics treats completion rates for undergraduate studies. College students graduate in four years, six years, eight years – in fact, six year graduation rates don’t reflect actual performance at all.

Non-traditional students make up a sizable population of more students these days, and conventional graduation rate calculations don’t account for them. What if it takes a student many more years to attain a degree than the criteria set by IPEDS? Well, that lowers graduation rates. What about transfer students? With tuition skyrocketing, many students are choosing to begin in community college and transfer into four-year institutions; they don’t always count (college must have transfer as college mission according to IPEDS). What about older, returning students, who may come into college with old credits, or who can only take courses part-time? Nope, not counted.

Education statistics are also notoriously unreliable for community colleges, because less than half of associate’s degree students are full-time or even concerned with whether they graduate on time. In fact, more than half of community college students are part-time and skip semesters. It has nothing to do with academic performance, but with the complications of life, such as family obligations, lack of student resources, and work. With a high proportion of female students, latino students, two or more races, and part time students, two year institutions are less concerned with retention rates and the college experience, or graduating at a “normal time.”

Changes in College Graduation Rates Over Time

According to the most current IPEDS data, things are actually looking up for college graduation rates. Between 1996 and 2010, the percentage of freshmen students actually graduating within 4 years went up significantly: only 33.7% of freshmen starting in 1996 graduated in four years, compared to 40.6% of freshmen starting in 2010. Naysayers have speculated that the increase is due to nothing but grade inflation – students passing classes and graduating without actually earning their grades – but higher college graduation rates are also a reflection of changing attitudes toward education. College students today have more support than they did 20 years ago, such as tutoring, accommodations for physical and learning disabilities, and financial advising. In addition, more older students and low-income students are going to college with high motivation and clear career goals – a contrast to the stereotypical wandering college student.

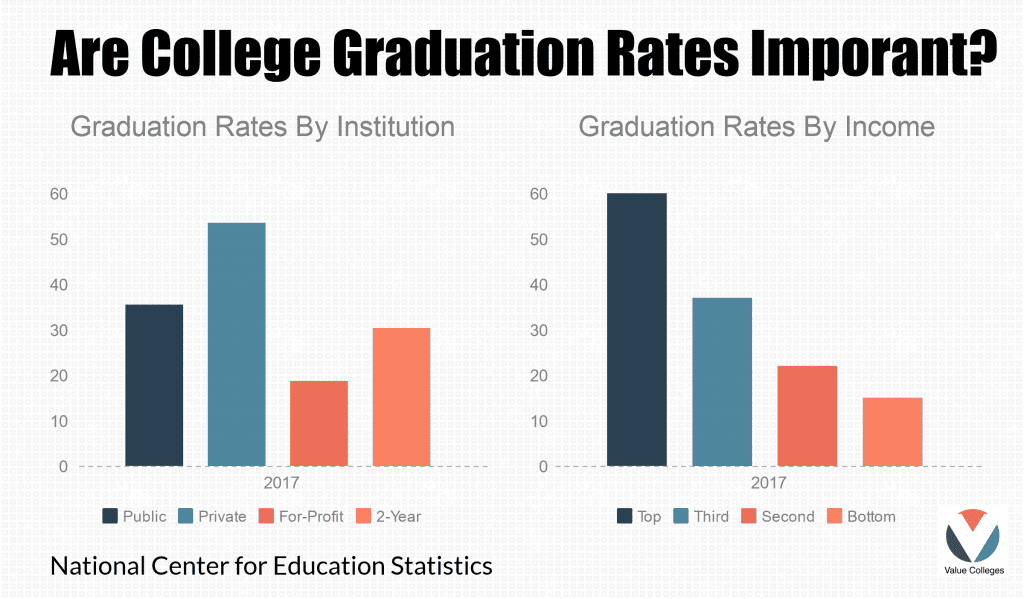

When it comes to community colleges and other 2-year programs, numbers have held steady for the past decade, hovering around 30% graduation rate for all 2-year institutions. This is to be expected; many community college students go to school never intending to graduate in the first place – they may just need general ed courses to transfer, or be working on a certificate that helps them on the job market. Transfer rates to 4-year institutions have increased as well, as the rising cost of college tuition has convinced many students to complete the first two years at the cheaper community college rate before transferring for their majors. The California State University system, for instance, encourages transfer.

What About Differences Between Institution Types?

Of course, there are massive differences between institutions; graduation rates for nonprofit 4-year institutions are incredibly higher than for-profits – 53.5% to 18.7%. That difference is due to many factors, but one of the main reasons is that for-profit institutions tend to target nontraditional students who are less concerned with graduating with a bachelor’s degree than with meeting specific career goals.

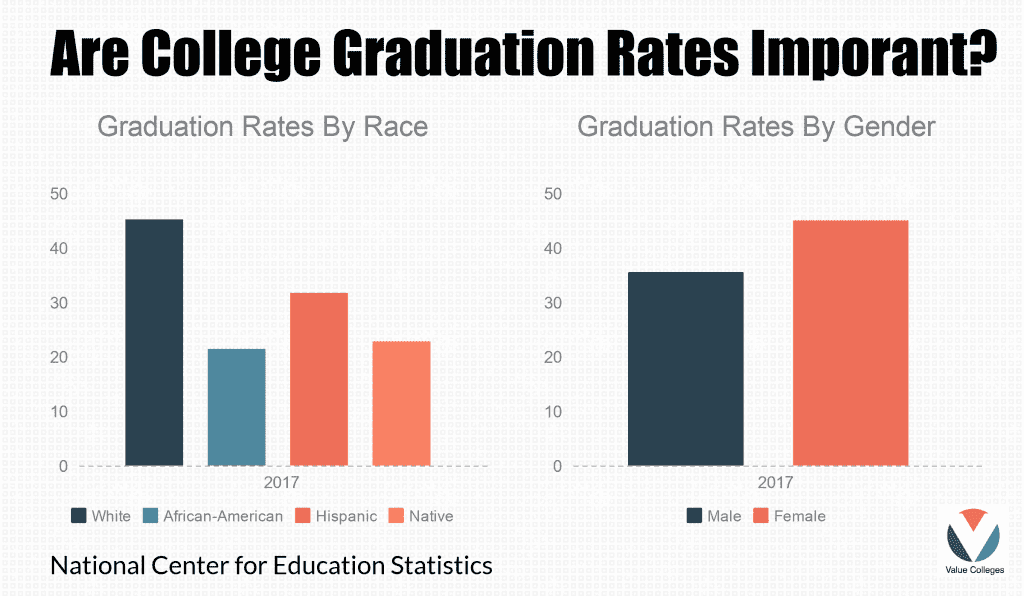

When broken up by gender, graduation rates are significantly different as well. Women graduate in 4 years at a rate of 45%, while the 4-year graduation rate for men is only 35%. Differences like this, combined with higher proportions of women going to college in the first place, have led many commentators to be concerned about a growing gender gap. On the other hand, the 6-year graduation rate begins to close that gap; the tendency for men to choose STEM programs more often than women – which typically take more than 4 years to complete – may help account for the difference.

College graduation rates by race have long been a concern for higher education experts, as graduation races for African-American, Hispanic/Latino, and Native American students have historically been much lower than that of White and Asian-American students. In almost all regions, types of institutions, and genders, college graduation rates by race are tied to socioeconomic status – poverty rates are higher among these groups, and a low-income background is one of the leading indicators of dropping out.

Why Do Students Drop Out?

How is College Dropout Rate by Race and Social Class Connected?

The NCES has found that family social class and graduation rates are closely tied. In fact, among the lowest economic percentile, only 14% of students graduated – compared to 60% of high-income students. In many ways, this is the largest concern for higher education experts, as social class and race are so commonly related in the US. In large part, the college dropout rate by race can be directly tied to family income and social class.

Why is the school dropout rate so much higher for low-income students? The difference can only partly be explained by the differences in academic background. In the US, most school systems are tied to neighborhoods, and school funding is tied to property taxes, meaning that schools in low-income neighborhoods have lower financial support and fewer resources for students. That leaves low-income students, particularly low-income minority students, with an academic preparation deficit that especially affects them when they reach college.

But preparation is not the only concern of low-income students. College dropout rate by race and social class is also directly related to the cost of college tuition in America. Tuition costs have doubled in the last 30 years – more than 213% between 1988 and 2020. That’s an increase far beyond the normal rate of inflation. When college is still the primary way for low-income students to move up in social class, higher prices price them out.

How Has Financial Aid Changed?

At the same time, major changes have happened in how students pay for college. Government grants have decreased; federal student loan interest rates have increased; and far more than three decades ago, students are on the hook for their own college tuition. All of these changes have fueled a student debt crisis that economic experts fear will be crippling for the financial future of Millennials and the next generation (who are now entering college).

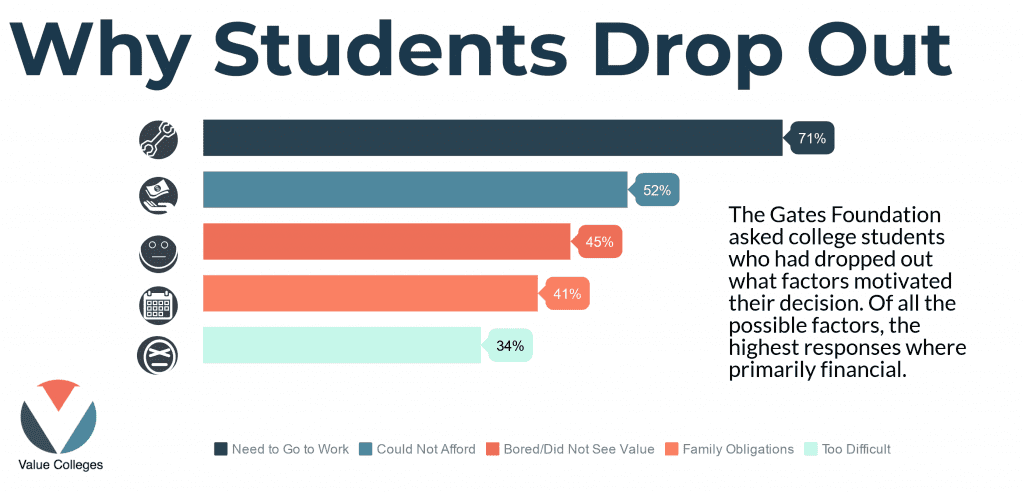

All of these concerns hit low-income students the hardest. For instance, changes to Parent Plus Loan qualifications left thousands of low-income students unable to pay their tuition, HBCUs were especially hard hit. Students are forced to go deeply into debt, without family income to help them, or to rely on grants and scholarships that may not be enough to pay their way. A Gates Foundation study a decade ago found that the number 1 reason students drop out of college is their inability to pay. For low-income students, who often have to work to support themselves in college, the conflict cannot be managed.

So Do College Graduation Rates Mean Anything?

It’s worth remembering Selingo’s warning: choosing a college based on graduation rate is like buying a car based on its safety ratings: it’s “just one measure of many.” Sure, it tells you something about the college, but don’t let it rule your choices, especially if you’re a non-traditional student. Educate yourself fully about any college you’re considering – not just graduation rates, but all of the factors that go into making an education worth your investment.

Related:

Top 50 Best Value Online Degree Completion Programs

Featured Programs

Aya Andrews

Editor-in-Chief

Aya Andrews is a passionate educator and mother of two, with a diverse background that has shaped her approach to teaching and learning. Born in Metro Manila, she now calls San Diego home and is proud to be a Filipino-American. Aya earned her Masters degree in Education from San Diego State University, where she focused on developing innovative teaching methods to engage and inspire students.

Prior to her work in education, Aya spent several years as a continuing education consultant for KPMG, where she honed her skills in project management and client relations. She brings this same level of professionalism and expertise to her work as an educator, where she is committed to helping each of her students achieve their full potential.

In addition to her work as an educator, Aya is a devoted mother who is passionate about creating a nurturing and supportive home environment for her children. She is an active member of her community, volunteering her time and resources to support local schools and organizations. Aya is also an avid traveler, and loves to explore new cultures and cuisines with her family.

With a deep commitment to education and a passion for helping others succeed, Aya is a true inspiration to those around her. Her dedication to her craft, her community, and her family is a testament to her unwavering commitment to excellence in all aspects of her life.